By Chelsey Shannon, editor

We’d seen their names—Laura and I checked, re-checked, triple-checked the spellings, diacritical marks, the preferences between initial and full middle name, the proper presentation of suffixation—truly countless times. We needed to ensure that everything was calibrated correctly, that the people who would one day hold the printed, complete version of SEEING BLACK: Black Photography in New Orleans 1840 and Beyond in their hands could accurately locate whichever image, whichever artist, they happened to be seeking.

Or, if they just wanted to flip through the pages and let the magic of chance, and this book, guide them, that would be cool, too.

Eventually, somehow, we finished this work, and I signed off on a manuscript not perfectly—never perfectly—but well scrutinized. Months passed; I didn’t know it as I slept, wept, worked on other books, took the occasional selfie (another, microcosmic seeing of blackness [mine])—I didn’t know it, but SEEING BLACK was slowly but surely manifesting at our printer. Then the books were on the boat. Then they were in boxes stacked in our office, our own mini Everest.

But the climb was already done. Now, it was just time to celebrate.

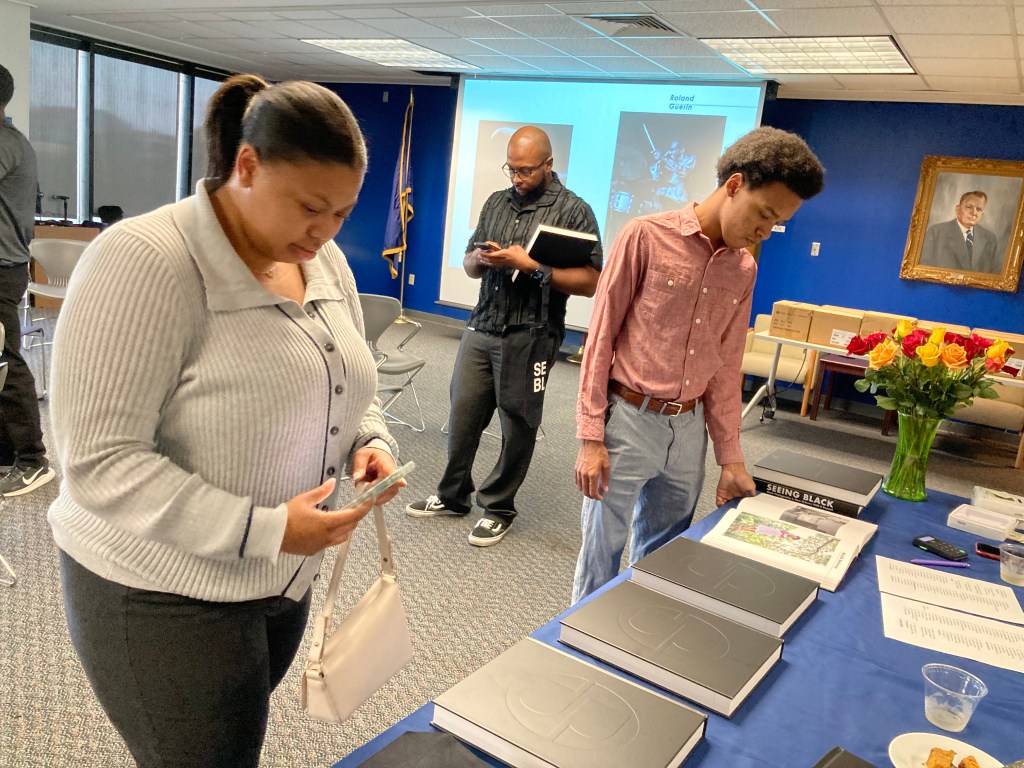

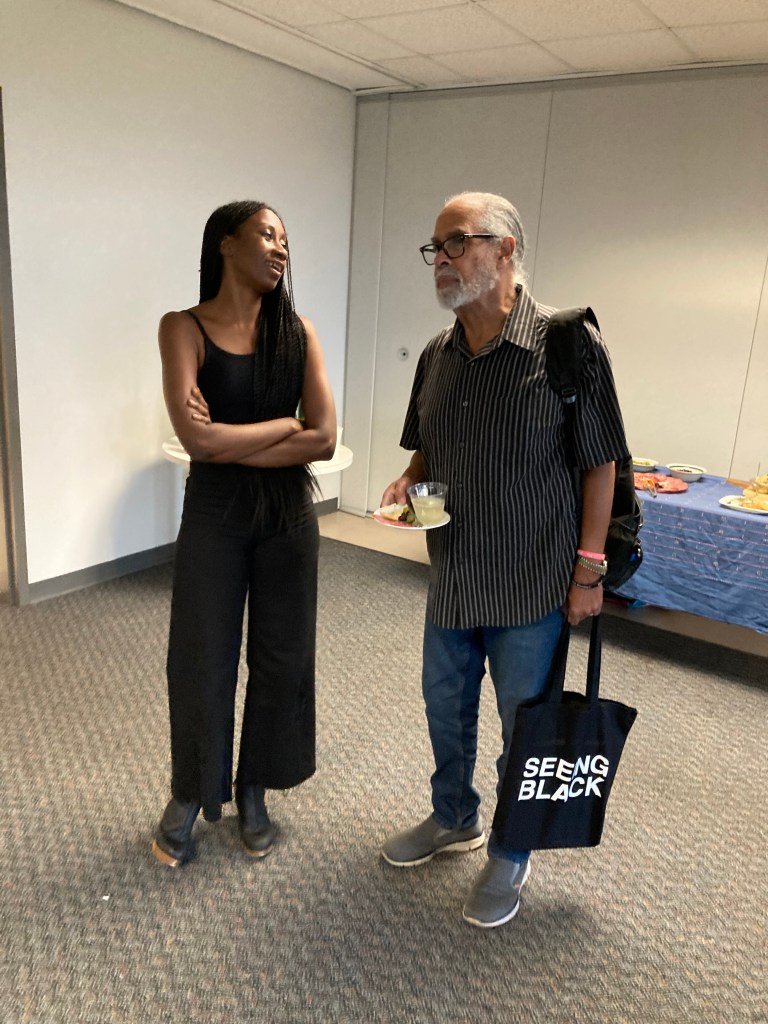

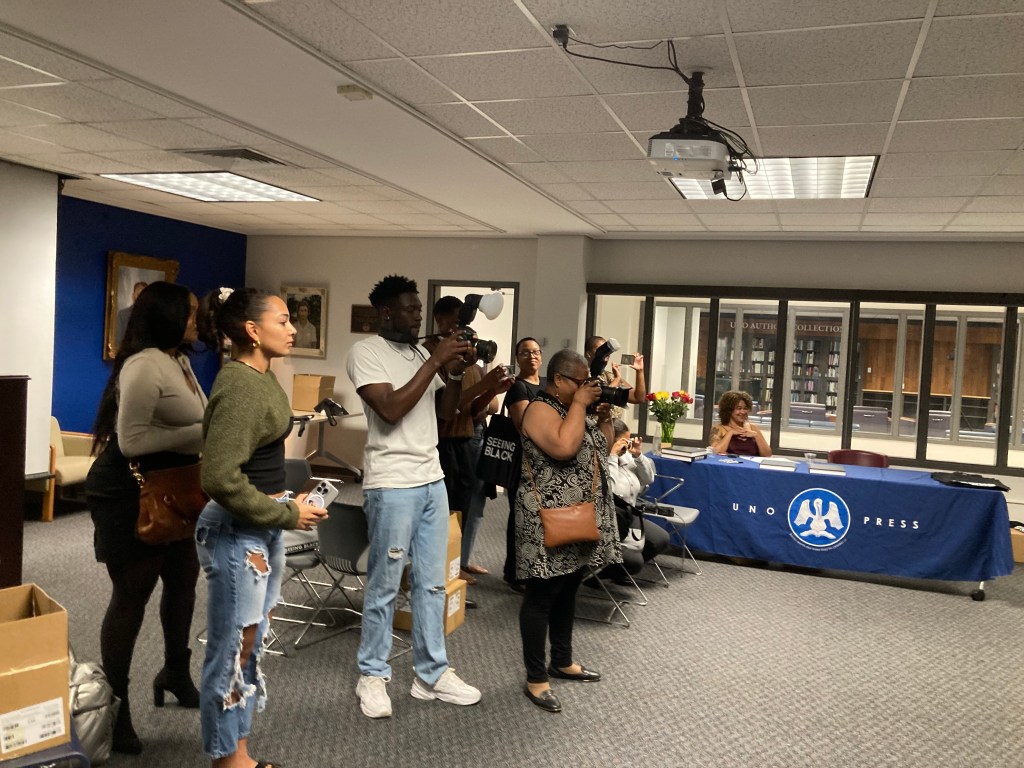

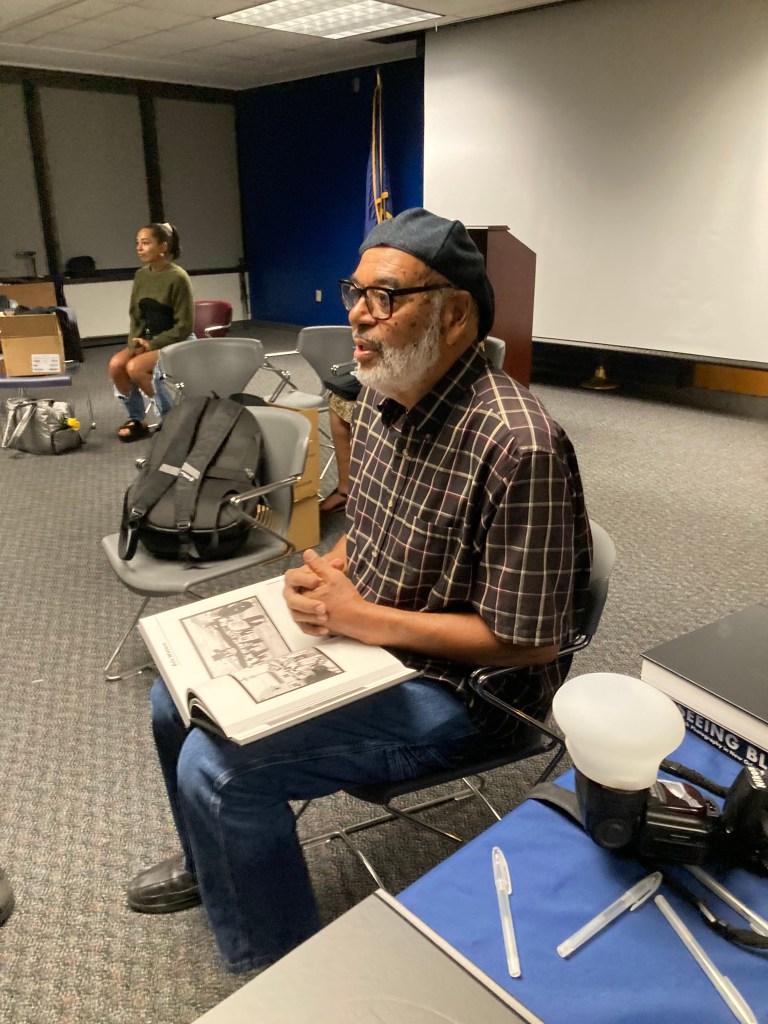

And that we did . . . first with a private reception for the photographers and three of the four members of SEEING BLACK, Shana M. griffin, Eric Waters, and Kalamu ya Salaam. What a group we were: photographers assembled together, some for the first time ever, some in renewal of decades-old friendship—and I finally got to match names to faces.

The topography of these connections was spoken when each photographer introduced themselves and said a bit about what it meant to them to be included in the collection. Currents of mentorship, collaboration, and inspiration rippled around the room in ways both delightful and unsurprising: the images of SEEING BLACK speak for themselves. But of course they belie an entire ecosystem of community, an artistry less tangible—that is, until its practitioners are all gathered in the same room.

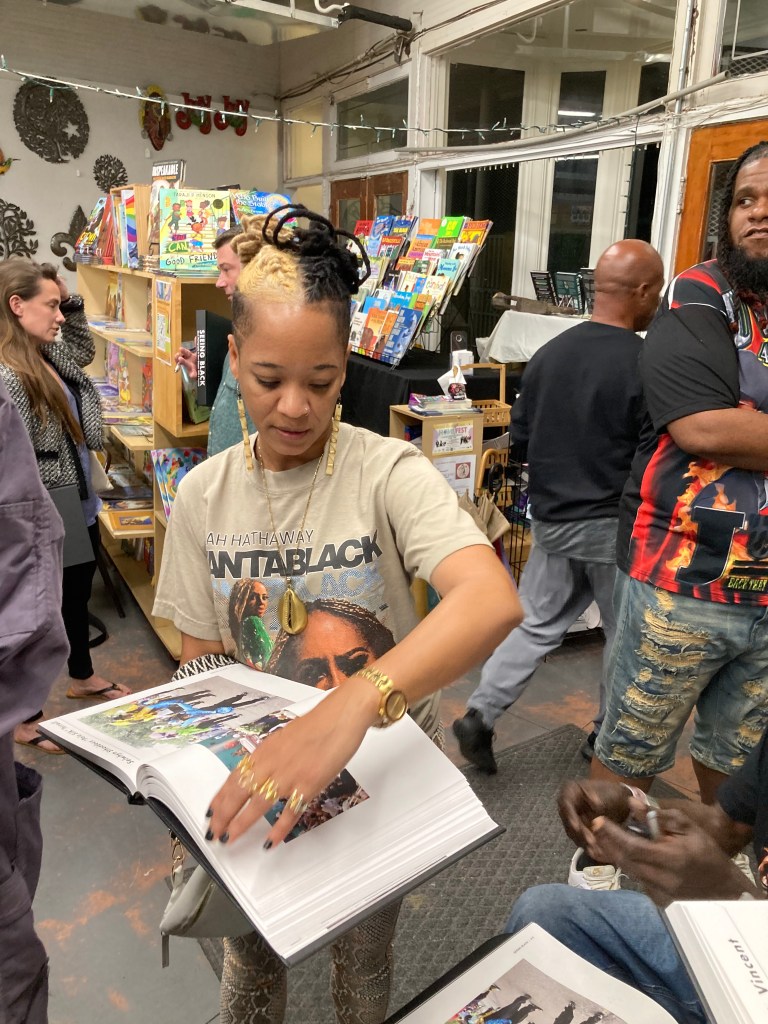

We did that again late last month, this time for the public launch of SEEING BLACK at Community Book Center, the oldest Black bookstore in town. This gathering quickly ballooned to SRO-status, so I posted up in a far corner as Kalamu, Eric, and the photographers settled in the front area of the bookshop, sitting in a circular formation with concentric rows, like the rings of a tree trunk. And while I’m not especially handy with a camera, resting at the periphery allowed me to behold some very beautiful things.

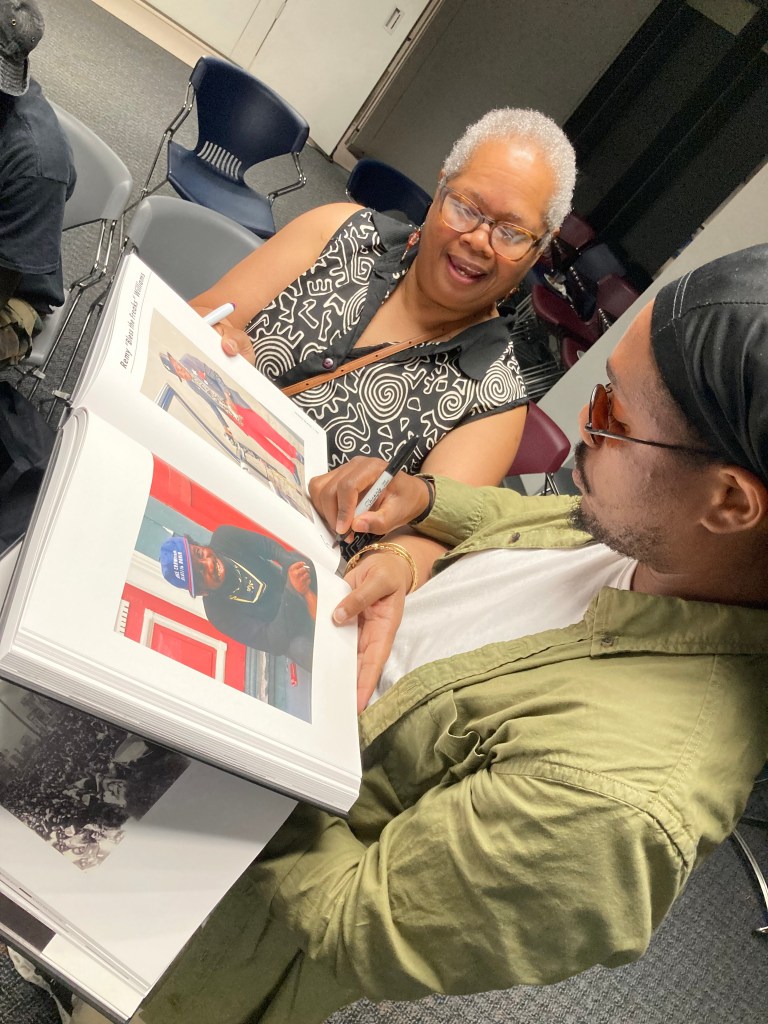

I saw hugs and kisses, faces lighting up as friends and collaborators and relations recognized each other. Per Eric Waters’ vision, copies of SEEING BLACK were being passed from pair of hands to pair of hands (for this is a book that requires both hands) in order to be signed like yearbooks, lending the gathering a further jubilant, anticipatory energy.

In the midst of this, Community Books founder-owner Vera Warren-Williams made space in the center for middle school students, participants in a program where they created books about their own family histories. Now, they received copies of SEEING BLACK as rewards for their work, after each taking the mic and introducing themselves to the room with the encouragement of Vera, resident community-building artist. “Photographers, everybody, make sure you sign the students’ books before they have to go home and do their homework!” she proclaimed at intervals.

Again, contributors were prompted to introduce themselves and say a few words about the project, as they wished. Dodie Smith-Simmons, not a photographer herself but among the party’s attendees, was invited impromptu to speak on her time as a civil rights activist with CORE. Later, I saw Polo Silk recording an interview with Smith-Simmons with his iPhone, the ado of the party their sonic backdrop. This was not long after Chandra McCormick and Keith Calhoun rolled in like rockstars, re-electrifying the air.

Among calls for pens and confirmation as to whose book was whose, so that they could be signed correctly, milling bodies sported a myriad of fashion statements, from power-clashing prints, camo colliding with boho, to slate-blue coveralls, to necklaces of supersize cowrie shells dipped in gold. Meanwhile, the youngest member of the gathering, a toddler in an all-candy pink ensemble, wove curiously through the crowd. This baby was plucked into parental arms as Kevin Jones spoke about choosing images for SEEING BLACK through a haze of grief, the invitation to contribute representing to him, at that time, much more than just another professional project.

“My father was my first mentor in photography—” he explained, only to be interrupted by the pink-clad baby’s emphatic cry of “Yay!!” The room chuckled and applauded this sweet serendipity, the youngster’s chance celebration of creative lineage.

Taking in the scene and feeling my feelings, I was reminded of Lorraine O’Grady’s 1983 performance art piece Art Is . . ., in which she and a crew carried large, golden picture frames around the African American Day Parade in Harlem, encouraging paraders (both performers and onlookers) to literally frame themselves, their everyday joy and candid self-expression, as art. I wished I could frame the entire book launch in a similar way: Art Is . . . (This Night at CBC in New Orleans). I suppose that’s what I’m trying to do here, with words instead.

From my seat near the table where folks paused to sign a book or two, I watched Malik Bartholomew flip to his photo spread to sign a fellow photographer’s copy. “You know, at first I wasn’t thrilled with them picking this image of mine,” he confided to me. “But, in the months since, he burned this suit. This piece of art doesn’t exist anymore.” Malik brushed his fingertips over the portrait of Wild Tchoupitoulas’s Flagboy Giz. “But I guess it still does in here.”

And this was always one of SEEING BLACK’s intentions, to be sure: to index and archive Black image-making in New Orleans, to set to heavy paper the thick roots and juicy fruits of this specific body of photographic artwork.

But, sitting in that room and taking in what Abram, afterwards, would call “some very rarified air,” I realized how much the project was about not just the artifact, but the living, breathing experience of which everyone at Community Books that night was part. It’s about what the artists of SEEING BLACK will continue to create in collaborations both historied and unprecedented, the up-and-coming artists they will nurture, the images they will continue to conjure and craft out of the lives they live.

The “and Beyond” in this book’s subtitle isn’t just thrown in there to sound fancy. It represents a profound infusion of vitality into the future of Black New Orleanians seeing and re-seeing themselves, and the intrinsic artfulness of that seeing. It is a promise that is always already coming true.

SEEING BLACK: Black Photography in New Orleans 1840 and Beyond is available for purchase now.